Audio Ripping and Compression

On how I like my MP3s to be compressed.

Bare in mind I wrote the following article back when I was an undergrad finishing my first year at Birmingham City University in 2013.

Original article is posted here.

Audio Ripping and Compression

Recently I’ve been really interested in the whole talk about audio quality. I really value ‘good’ quality recordings and cherish the moments when I have access to these, but I was never too obsessed about it. Everyone will have their own interpretation of what sounds good anyways. Ha! And that is what’s really interesting.

While I do not lament when I sometimes listen to 128kbps Mp3 files, I believe it is important to be able to compress audio files correctly because the poorly processed ones can ruin our ears forever… Or, for example, negate the advantages of an expensive speaker set that we may use.

So I will present a method of audio ripping that will allow anyone to be left with a really good quality compressed files, as well as a little experiment, which hopefully will once and for all, save me from wasting my time thinking about differences in quality between an uncompressed audio file and a ‘correctly’ compressed Mp3 file.

The first step is to find a CD that you would like to burn and then check it for any possible scratches. CDs are made from polycarbonate plastic (Macrolon) which is a sturdy and strong material that sadly scratches quite easily. The designers saw that coming and planned for it. The Red Book Standards for Audio Compact Discs enforces an error correction system that allows CD players to deduce a surprising amount of data based on the data which comes before and after a scratch.

Furthermore, the data is not stored on the shiny part of the CD, but is actually stored on the label side (the program area). The CD player’s laser has to make its way through a layer of plastic till it reaches the disc’s data. So after all, a small scratch on the back surface of a CD is not as dangerous as it may seem.

OK, so if you got that far and think that few facts about the program area of a CD will spoil this reading then just skip to the next paragraph… The program area of a CD also conforms to Red Book standards. Data is stored internally in a series of “bumps” known as “pits”. These pits are located in a single spiral track of TDM (time-division multiplexing) data. The data pits come in 8 different lengths: from 0.833μm to 3.56μm. The varying length and distance between the pits is how the digital audio information is stored in NRZI (the NRZI stands for non-return to zero inverted and is one of the most popular languages used for Pulse Code Modulation (PCM)).

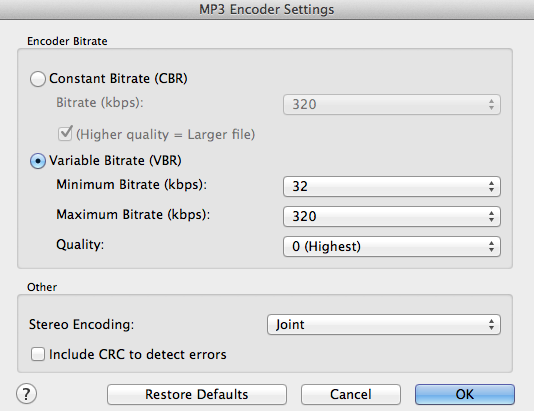

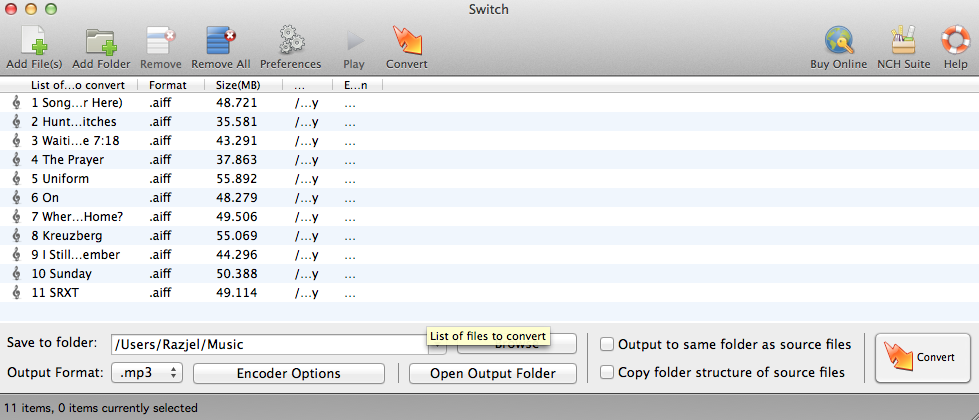

So, once you’ve chosen a CD that you are satisfied with, you will need a piece of software that will allow you to rip and compress it. I’m using Switch, which works both on pc and mac. Once you have opened any reasonable audio file converter software then I would take a moment, and poke around the encoding tab. It should look like this.

These are the settings I’d use for creating high quality Mp3s. I’ll write a little bit about the details after.

Encoder itself is one of the applications to encode audio to Mp3 files so they take far less storage space. This is called lossy compression. On that note, many people think compression equals a reduction in data and quality let say Mp3, MPEG, DTS and JPEG. Well, this is not always the case. Few examples of lossless compression: ZIP, RAR, TIFF, MLP. But back to the encoder. The encoder uses two different compression methods namely, CBR or VBR (see above settings).

CBR stands for constant bit rate, which basically means that you tell the encoder to express every second of audio with a certain number of bits, and it does just that. It will give every single second of audio the same amount of space. There is nothing really bad about this method, it is simply very wasteful and produces bigger file sizes than VBR. Hence, somebody smart came up with another method called VBR.

VBR stands for variable bit rate and is the most commonly used encoding type. With VBR the encoder considers every section of audio very carefully and decides how many bits it would take to encode it with the desired level of quality. This means that the bit rate can actually drop to almost nothing in the parts where there is silence, shoot up to high hundreds when the song starts, and peak at the limits of the encoder during particularly delicate passages.

Mode in the stereo encoding section, I would leave on joint stereo as it offers better quality. In the joint stereo the encoder can spend the available bits more efficiently than normal stereo mode. There is a technique involved known as joint frequency encoding, which functions on principle of sound localization. It stores one channel as the difference from the other as opposed to an entire second audio stream.

Quality is the deceiving one. It basically tells the encoder how many shortcuts can it take during the analysis and compression process. When (q=0) the encoder does everything super accurately. When you set it to 9 it will do everything in a more ‘clumsy’ manner. The technology has moved by quite a lot since 1993, so nobody would really use low quality encoding today.

CRC stands for a cyclic redundancy check and is an error-detecting code commonly used in digital networks and storage devices. I don’t know what real advantage it will bring to this compression process so leaving it alone, and unchecked should be completely acceptable.

If I’m using a VBR then I want the encoder to have access to the widest range of bit rates possible. The minimum should be at 32 and the maximum should be at 320.

The output sample rate is not shown in this window but I know it is going to be the original CD sample rate, which again thanks to the Red Book Standards, is said to be 44,100kHz.

OK, lets get down to business.

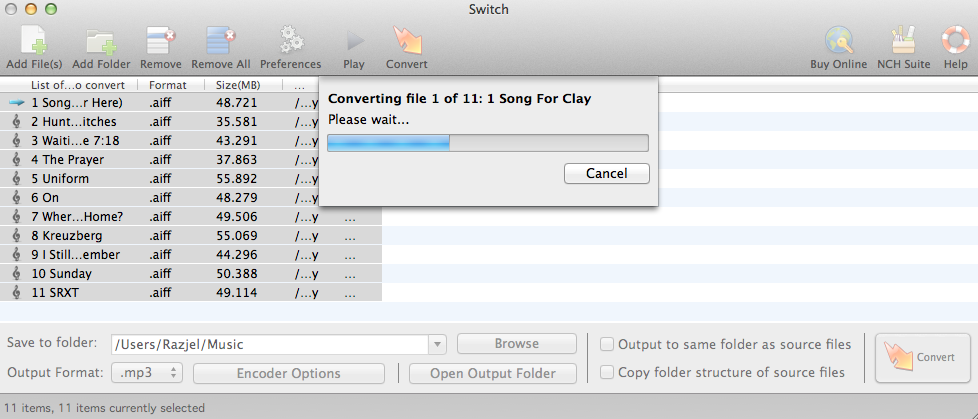

Above you can see all loaded tracks in .aiff file format. All that’s left to do is to click convert and all the magic will be done for us.

The conversion of all the files will take a while. After the conversion finishes, you are done. You’ve just converted losses CD files into a ‘very good’ quality lossy files. OK, but that’s still just talking. So in the next post I’ll test how good they actually are when compared.

Maciek